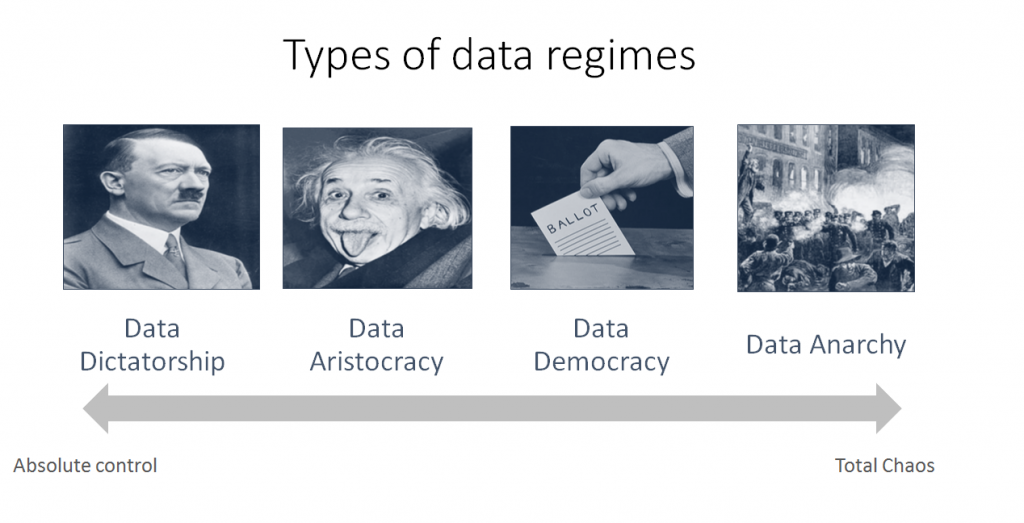

In Part 1 of this series, I spoke about the different types of data regimes. In this post, I will examine the pros and cons of data democracies and provide guidelines for how you can be successful.

Customers often ask me, “Is there an approach or data regime that is generally superior?” It would seem like a data democracy is the obvious choice for most scenarios. Vendors have been touting “BI for the masses” for years – they must be right. Right?

Wrong.

Firstly, it’s confusing because concepts like, “single version of the truth” and “golden copy of data” have no place in a democracy. These concepts belong to dictatorships. Democracies have multi-faceted and personalized versions of the truth. For e.g. A metric like “Revenue” may have multiple – yet correct – definitions based on the context of the observer.

Secondly, there are negatives, including a perception that decision making slows down. Analysis paralysis sets in. Have you ever heard of committees taking decisive action?

Another negative is that democracies emphasize quantity over quality. More data in the hands of more people does not imply better quality decisions. Sometimes organizations can get lost in minutiae, like when Google decided to experiment with 41 shades of blue. Group think, and second guessing are also “traps” that data democracies fall into.

Data democracies are hard to create and even harder to sustain. But despite all the drawbacks, there are a few significant long term advantages.

Higher corporate IQ & sustainable innovation

For organizations, it’s not important how clever individuals are; what really matters is how smart the collective brain is.

Creating a data-driven democracy is a great way to raise the IQ of the collective brain. Because of the way information flows in a democracy and connects people with shared interests, it is analogous to how the neurons in your brain work. More interconnections are good – data can flow through multiple pathways. This in turn provides the ideal substrate for ideas to have sex and innovation to flourish.

In other words, data democracies make for smarter, more innovative organizations.

Highly engaged & motivated teams

Democracies help galvanize tribes. People with similar interest can collaborate to solve problems like never before. The idea of self-assembling groups, working together to resolve problems based on shared interests, is powerful.

Being a part of a tribe also contributes to a sense autonomy and purpose, which according to Dan Pink, are keys to solving the puzzle of motivation.

These advantages are critical to long term competitiveness. However, you can’t mandate a democracy – you have to let it blossom.

Some guidelines that may help:

1) Lower the bar

Allow decision making to take place at the lowest level in the organization possible. Employees closer to the ground have tacit information and context that senior managers, more removed from the situation, simply don’t have. While this sounds like you are lowering the quality of decision making by allowing lesser qualified people make decisions – you end up with not just higher quality but faster decisions and higher morale.

2) Give rights

Provide “decision rights” for all employees. A data democracy is meaningless without “decision rights.” Those with the most complete knowledge of the situation at hand should make the decision. In the past senior managers had more data and could second guess lower level decisions. Providing “decision rights” will speed up decision making and prevent the trap of “second guessing.”

3) Share

Share access to corporate goals, strategies, priorities, and policies. This will help provide front line workers and managers a better framework for decision making. Otherwise, they are just cogs in a machine and will not benefit from having more data.

4) Diversify

Avoid group think by adding diversity. Not biological or racial diversity for the sake of it, but diversity of background, perspective, experience and thought. This will prevent an echo chamber of like-minded people taking poor decisions.

5) Let new leaders emerge

Just as the finance organization manages money, and HR is responsible for intellectual capital, a new information organization will emerge, outside of IT, led by the Chief Data Officer (CDO). Gartner has recommendations and estimates that there are currently about 50 established CDOs out there already and expects this to grow to 20 percent of enterprises worldwide.

There is no one size fits all. The best run organizations need to find a balance. But for companies who care about motivated employees and innovation more than short term results, getting a healthy dose of data democracy is the way to go